[♪mellow music♪] [The Many Faces of Traumatic Brain Injury] [♪♪] A warm greeting to you all. My name is Mary Hibbard. I am a Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. I’m also the Training Director of the Research and Training Center for Traumatic Brain Injury Interventions, which is funded by the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research. A core part of our training mission within this funding is to educate medical and mental health professionals as well as those professionals in training about traumatic brain injury or TBI. Traumatic brain injury has been called the silent epidemic, and today it presents as one of the major undiagnosed health problems in America. The DVD you will be seeing today is entitled “The Many Faces of Traumatic Brain Injury.” The program has three primary goals. The first is to provide basic education about traumatic brain injury– its presence, its etiology, where it is diagnosed correctly and how often it is misdiagnosed. The second objective is to highlight the importance of screening for traumatic brain injury in individuals that you may be seeing or will be seeing in your own clinical settings.

The third is to understand the long-term challenges of living with a brain injury and, perhaps more importantly, how you will need to accommodate the survivor of a brain injury who is faced with these lifelong challenges. The presenters you will meet in this DVD are all individuals who have experienced either traumatic brain injury or acquired brain injury. The individual with severe traumatic brain injury, Tricia, is an individual whose traumatic brain injury was correctly diagnosed at the time of her hospital admission. The brain injuries of two individuals with moderate to mild injuries, however– that is Timothy and Kathleen–their brain injuries were not correctly identified at the time of their hospitalizations. Neither was Beth, the individual with acquired brain injury. The struggles of these individuals to obtain proper diagnosis of their traumatic brain injury and, more important, needed treatment for their cognitive challenges are clearly illustrated in their own stories. These survivors provide a personal glimpse of the long-term challenges of living with brain injury. They also offer wise counsel for you as medical and mental health professionals or professionals in training which will hopefully be beneficial within your ongoing practices now and in the future.

At this point, I would like to turn the DVD to Dr. Brian Greenwald who will be providing some basic facts and information about traumatic brain injury. Thank you. I’m Dr. Brian Greenwald, Assistant Professor of Mount Sinai Medical Center Department of Rehabilitation. Today we’re going to be talking about traumatic brain injury. To start we’ll define what a traumatic brain injury is. Traumatic brain injury is an underrecognized problem but a major public health epidemic. The National Head Injury Foundation defines traumatic brain injury here as an insult to the brain caused by an external physical force that may produce a diminished or altered state of consciousness. I’ll underline here “external physical force” and “diminished or altered state of consciousness.” This can result in impairments in cognitive abilities or physical function but also can result in disturbance of behavioral or emotional function.

These can be temporary problems or represent long-term functional disability. The CDC in 1995, trying to be more succinct, put traumatic brain injury as an occurrence of an injury to the head with one or more of the following problems associated: decreased level of consciousness; amnesia; skull fracture; or other objective neurologic or neurophysiologic abnormalities. I’d like to emphasize also what traumatic brain injury is not. These are other problems that people have related to their brain, including mental retardation, brain tumors, organic psychiatric illnesses, genetic neurologic illnesses or stroke. All these put together are common problems but are not traumatic brain injuries. Other names that are commonly used for traumatic brain injury include TBI– and that will be the expression I’ll be using through most of this video– concussion, acquired brain injury– which includes a number of other types of brain injuries– a closed head injury or a head injury. Looking at this slide, we can see that traumatic brain injury is a very common phenomenon overall.

in comparing it to other disease processes that we’re familiar with. You can see here multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, HIV and breast cancer, and traumatic brain injury up here–million cases per year. These are numbers that are put together by the CDC, and they’re estimates for the annual incidence of traumatic brain injury. These are recent data from the CDC talking about the causes of traumatic brain injury. Of that million traumatic brain injuries that we were talking about, where are people getting those traumatic brain injuries? This newest information includes emergency department visits, deaths and hospital admissions.

You can see here falls have become the top cause of traumatic brain injury at about 28 percent, with motor vehicle accidents trailing behind at 20 percent. With regards to incidence, each year about 50,000 people die from a traumatic brain injury and about 80,000 to 90,000 people experience the onset of long-term disability related to a traumatic brain injury. As far as prevalence, the CDC estimates that million Americans live with the secondary causes from traumatic brain injury. When you calculate that there are about 300 million people in the country currently, that means that about 2 percent of Americans currently live with disabilities relating to traumatic brain injury. Talking about pediatric traumatic brain injuries–those that are identified– it’s really a leading cause of death and permanent disability in children and adolescents, a leading cause of death in children under the age of 5. And about 430,000 children under the age of 15 have a traumatic brain injury every year. More than half of all traumatic brain injuries occur in people under the age of 25. Let’s talk a little bit now about pathophysiology, what’s actually happening to the brain when someone experiences a trauma to their brain. We’re going to break it up first into primary injury, and we’ll look at focal injuries like contusions and hemorrhages and missile wounds from, let’s say, gunshot wounds and diffuse injury like you might see in diffuse axonal injury.

In this slide we can see some of that primary injury, and we can see injury most commonly to both the temporal lobes and the frontal lobes. These lobes are forced against the front part of the brain and the bony skull base secondarily are common areas for contusions. In this next slide we can see both the coup and contrecoup injuries. After the brain has hit the anterior portion of the skull, it then reflects back and goes on to the posterior portion of the skull where you may have damage to the occipital lobe or the parietal lobe. This slide shows diffuse axonal injury. In an acceleration/deceleration injury that you might see in a high speed collision, the brain goes forward and backwards and there are rotational forces on the brain, and this can cause disruption of the axons.

This certainly accounts for some of the deficits that we see after traumatic brain injury. Beyond these primary injuries that we’ve just discussed, there are a number of secondary injuries that can occur to the brain also. Cerebral edema, increases in intracranial pressure that lead to ischemia, infarction, late hemorrhage and anoxia are all things that we try to avoid medically after the person has had a traumatic brain injury. Next I’d like to introduce Tricia Mieli, who is going to talk about her experiences after a severe traumatic brain injury. Hi. I will give you a brief history of my severe brain injury, tell you a bit about the length of treatment that I received and then give you my perspective on long-term challenges.

It was 18 years ago that I was beaten unconscious, raped, bound, gagged and left for dead in New York City’s Central Park. I became known in the media as the Central Park Jogger. The severity of the beating to my head that night resulted in a severe traumatic brain injury as a result of the diffuse axonal injury. I was in a state of the most profound form of shock, Class IV hemorrhagic shock, and I was also in a deep coma for 12 days. On the Glasgow Coma Scale I was only a 4. As a result of the brain injury, I have absolutely no memory of any of the events from the night of the attack until just about six weeks later. So I don’t remember going running, the attack, being raped or most of the time in the acute care hospital in New York City. My treatment consisted of seven weeks in the acute care hospital followed by a little more than five months of formal inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation in Connecticut. The care I received in those first few weeks was instrumental in my recovery. I don’t remember most of it, but a nurse that I had who used to hold me in her arms when I became agitated to calm me down told me something many years later that I think is important to share.

She told me that one of the things she thought shouldn’t be done was when physicians would come into my room and talk about my condition or problems around my bed. She felt that they should go to a conference room because she feared that I would understand what they were saying. She told me, “You may not have been able to talk, “but there was nothing wrong with your ears.” “And besides,” she said, “what’s the point of saying, ‘She can’t’ “or ‘She’ll never’ or ‘She won’t.'” She feared that I would believe them. In the early days after the attack, doctors weren’t sure if I’d regain any of my cognitive function. I’m so happy that I’ve made great improvements. But I still can be overwhelmed and have difficulty prioritizing. Sometimes I can be distracted when I’m in the middle of something. And oftentimes I get very nervous in a meeting that I won’t be able to communicate, and that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But coming to terms with these deficits will probably be an ongoing challenge. Neuroplasticity is my favorite word. I continue to see improvements in my physical abilities, my cognitive abilities and, perhaps most importantly, in my ability to accept myself. This for me is healing. Post-brain injury I’ve enjoyed a full life, in large part because of the tremendous care that I’ve received all along the continuum of care. And I admire your career choice because I know what a difference your work will make to others just as it made to me. Your support, your care, your trust will help to create an environment that unleashes a power we each have deep inside of us to heal and come to terms with whatever our situation is. This isn’t in your textbook, but I believe that with support and even love there is hope. And from hope possibility emerges, no matter how dire the situation. To me, this is what keeps life moving forward. And you will be a part of that process. Let’s now talk a little bit about moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. TBI severity is measured by a number of scales.

The most commonly used is the Glasgow Coma Scale, which you might be familiar with from the emergency department. But length of loss of consciousness and length of post-traumatic amnesia– post-traumatic amnesia as an antegrade amnesia– are also common measures of severity of traumatic brain injury. These are measures of severity but don’t necessarily measure the person’s impairment in function. The Glasgow Coma Scale, as I mentioned, which is one of the most common scales used for measuring severity of traumatic brain injury, looks at three different components.

There is eye opening, best motor response and best verbal response. It’s generally done in the emergency department after resuscitation. It ranges from 3 to 15. Everybody gets at least 1 in each of those categories just for showing up. The higher the score, the better the level of consciousness. Moderate traumatic brain injury is considered a GCS of 9 to 12. A severe traumatic brain injury is someone with a GCS of less than 8. The people with moderate to severe brain injuries are much more likely to be recognized early and are more likely to be hospitalized and to go through rehabilitation. There are number of guidelines to help you when someone after traumatic brain injury comes into the emergency department.

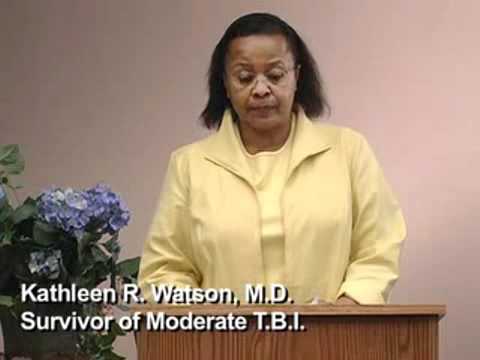

As far as deciding who should get a CAT scan or an MRI, there are a number of guidelines to look at which will help decide who should get a CAT scan that may look for early hemorrhages. With regard to the treatment of someone with a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, the Brain Trauma Foundation has some guidelines, including the prehospital management of traumatic brain injury and the management and prognosis of severe traumatic brain injury that was most recently updated in 2003. Next I’m going to introduce Dr. Kathleen Watson and Timothy Pruce, who are going to talk about their experiences of initially undiagnosed traumatic brain injuries that were moderate to mild in severity. I was a board certified practicing physiatrist trained in physical medicine and rehabilitation in New York City.

I was getting ready to take over the management of the Mona Rehabilitation Hospital in Kingston, Jamaica, when tragedy struck. I went out to walk for physical exercise one afternoon when I was stuck by a motorcycle. I was taken to hospital by passersby and eventually admitted to the orthopedic service. A nurse kindly washed me and transferred me to the bed where I remained, unattended, overnight until the following morning when the orthopods were making rounds and they identified me by saying, “Ah, this is Dr. Watson.” I finally got to the operating room the next afternoon. On recovery from the anesthesia, I went into respiratory arrest. I was in the ICU on the respirator for approximately seven days. I woke ten days later to find myself in the hospital bed where I had trained as a medical student in Jamaica. The next ten months were filled with surgeries, debilitation and later exercises trying to recover my strength.

My life became the medical care of self. But this was with help. I was a changed person to people who knew me before the accident. After the accident, I was a slow walker with crutches, slow in mentation and in social response. I looked physically weaker but normal to the naked eye– that is, there were no body parts missing. Psychometric testing done later at my insistence indicated that I was functioning at the 50th percentile. It was felt that I was estimated to have been functioning at the 90th percentile before the accident. I have been able to control my environment in that I set the pace of my involvement.

As a result of this, my performance seems to many that I have recovered. However, I know how to mask the deficits. This presents a challenge to the unsuspecting as many mild to moderate head injured are in the society and they are paranormal. As the society ages, the numbers will only increase. My progress and recovery continues 11 years later. Most recently, I have resumed my weight training and resistance program along with cardio work. It seems to me that there has been a change in my cognitive function. Compared to the accident, there are still some deficits of the higher cortical functioning, some of the executive skills. My sense of humor is slower, my problem solving ability is slower, my response to conversation is slower. There are still some memory lapses. I mask these very well, however. Most importantly, I do not beat myself but press on and keep going.

I regard the cup as half full, not half empty. Thirteen years ago I was driving to work, and as I was driving I heard sirens. I could not tell where they were from. So I was unable to pull over to the right to let the vehicles–wherever they were–go by. So I had to pull up to the intersection at the green light. The vehicles were actually coming from my right to my left in front of the boulevard in front of me. The car behind me failed to hear the sirens and failed to notice that traffic had stopped, and he rear-ended me. I lost consciousness briefly and was taken to the emergency room. On admission to the emergency room, medical attention was focused primarily on my injuries to my spine and my right side.

I had no memory of the accident, but this fact did not seem important to the people in the ER. I was released a few weeks later from the hospital. I had recovered somewhat from the paralysis on my right side, but I still had a lot of weakness. I was prescribed physical therapy to increase my right arm strength and walking as an outpatient. While physical therapy was helpful, I noticed new problems with my memory. I was easily disoriented, I was slow to process information, I was very fatigued and had what was later described to me as petit mal seizures.

Due to continued functional difficulties, my mother came out to help oversee my care. At that time, she took me to a variety of specialists and doctors to see what was wrong with my memory and other deficits. The first round of physicians and doctors attributed all my problems to being psychological and suggested I just needed a good therapist. I tried to go back to work approximately two months after the accident only to discover that everything I had previously known was alien to me. I couldn’t find my office, I had to be reintroduced to my staff members, I kept forgetting conversations, I kept forgetting meetings and I found out that I would completely shut down by midday due to fatigue. After two weeks of attempting to work, I became aware that it was obvious I could not continue in this capacity due to my deficits and had to leave my position.

About four months after my injury, my physical therapist directed me to a psychologist who was working with TBI patients. That was the first time I had a neuropsychological evaluation and was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury. I attended a six-month day program after I was diagnosed. I then moved out of state so that my family could take better care of my needs. I lost most of my friends at that time due to the relocation but also to their discomfort with the changes in my demeanor post-injury. I continued my rehabilitation in various day programs for the next three years. Over time I gradually realized that my life was going to be a lot different post-TBI and that I would be somewhat different from before. I now realize that I don’t know when or if I will be able to return to work full time in any capacity. I continue to struggle with a variety of cognitive challenges, including mental fatigue, memory difficulties, problems with reading comprehension, difficulty tracking verbal communication and a tendency to become overwhelmed in busy situations.

I have to really work hard to appear normal, which further compounds my fatigue. Next let’s talk about mild brain injury. I want to stress the importance that a concussion and a mild brain injury are really the same thing. With regards to level of severity, certainly the milds represent about 85 percent of all traumatic brain injuries, and moderate to severe is about 15. It’s the mild, though–this 85 percent–that’s most likely to go undiagnosed or undertreated. Just to talk about the definition of mild traumatic brain injury, the ACRM put together this definition in 1993, which is still the most commonly used definition– a traumatically induced physiologic disruption of brain function with at least one of the following: loss of consciousness; loss of memory of events immediately before or after the injury; and altered mental status at the time of injury or focal neurologic deficits. I think it’s important to recognize that a loss of consciousness in itself isn’t the important thing. To define a traumatic brain injury, particularly a mild traumatic brain injury, just an alteration in mental status at the time of injury would be considered a mild traumatic brain injury.

With regards to some of the measures of severity of traumatic brain injury, a loss of consciousness less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma score of 13 to 15 after 30 minutes and post-traumatic amnesia, that antegrade amnesia that we talked about, of less than 24 hours are all some of the defining severity characteristics of someone with a mild traumatic brain injury. It’s the mild traumatic brain injuries that are most likely to be treated in the emergency department or the MD’s office that often go unreported or undiagnosed and, unfortunately, untreated.

Remember that someone with a GCS of 15, which is the highest score, does not mean that the person did not have a traumatic brain injury. Someone with a negative CAT scan or someone with a negative MRI does not mean that the person didn’t have a traumatic brain injury. And unfortunately, the GCS, although it certainly has its good qualities, does not necessarily capture the symptoms related to a traumatic brain injury, especially a mild traumatic brain injury which, again, is the same as a concussion. This slide shows the pyramid of what happens to people with traumatic brain injury. On the top here we can see that about 50,000 people die each year from traumatic brain injury, about 235,000 are hospitalized each year, over a million emergency department visits related to traumatic brain injury. But there are many more who receive either other medical care or no care after their traumatic brain injury. Official estimates don’t include the estimated 439,000 traumatic brain injuries that are treated by physicians during office visits and does not include the 89,000 treated in the outpatient settings.

These numbers are from the CDC. Also, with regards to undiagnosed traumatic brain injuries, these estimates do not include a traumatic brain injury for which no medical advice was sought, and this may be up to 25 percent of all mild to moderate traumatic brain injuries. This also, unfortunately, does not include data from the federal, military or Veterans Administration hospitals. A lack of identification leads to misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, a mismatch between treatment and cognitive impairment, academic and vocational failure and increased psychopathology. Where do we find some of these people who go undiagnosed after traumatic brain injury? These are settings where certainly people are at a higher risk overall: domestic violence shelters; in professional and leisure sports, and we’ll talk a little more about that; in substance abuse settings; in psychiatric and mental health settings; in vocational rehab settings; in geriatric settings; in prisons, unfortunately; and in the welfare system; and more and more we’re learning in the military. With regards to sports and traumatic brain injury, there are a number of sports where traumatic brain injury is a common experience. Certainly football–and we’ve heard many stories in the news lately about football– boxing where the goal is actually to get a knockout and give someone a mild brain injury or a concussion, hockey and soccer and bicycle riding and skiing and snowboarding and roller skating and field hockey are all sports where we commonly see people with concussions or mild to moderate traumatic brain injury.

With regards to football and traumatic brain injury, a recent study looking at college-aged kids found that about 5 percent of these football players sustained at least one concussion. About 14 percent of those who sustained one concussion sustained a second injury during the same season. And players who sustained one concussion were three times more likely to sustain a second concussion in the same season. And only about 8 percent of those who had these injuries involved a loss of consciousness, again showing how it’s not the loss of consciousness that’s the important part, it’s the altered mental status that’s the important part after a mild traumatic brain injury. About 30 percent of these players with concussion returned to participation on the same day of injury. It’s very controversial as far as return to play after a traumatic brain injury in sports, and certainly this is an evolving knowledge base. With regards to pediatric traumatic brain injuries, the majority of pediatric traumatic brain injuries are mild, especially in the age range of 5 to 14. It is a high incidence event, though. With regard to identification issues in pediatric traumatic brain injuries, children with traumatic brain injury who remain unidentified or misidentified are more likely to fail or fall behind in school.

Injuries occurring before milestone attainment in the pediatric population may result in those milestones never being achieved. And outcomes overall are more positive when children are identified and treated early. As far as the elderly and traumatic brain injury, this is the largest growing group of patients sustaining traumatic brain injury. Certainly people who are elderly are at a high risk of falls, they may be on medications that increase their risk of falls, they have decreased balance and decreased strength, they may be on blood thinners such as Coumadin and aspirin that put them at a higher risk of injury after a fall and, unfortunately, elder abuse all play roles in the higher incidence of traumatic brain injury in the elderly population.

There’s been greater and greater awareness of war veterans with regards to traumatic brain injury. Traumatic brain injury has been the signature injury in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars due to the nature of the weapons being used. Most traumatic brain injuries are due to the improvised explosive devices, also called IEDs. Most of these traumatic brain injuries are mild in severity but, unfortunately, our veterans may be exposed to multiple explosions and secondary mild traumatic brain injuries. There may be significant disability from these traumatic brain injury related symptoms. Next I’d like to introduce Dr. Beth Ackerson, who experienced an undiagnosed acquired brain injury from encephalitis and meningitis. You’ll see many of the common symptoms that she had that overlap with traumatic brain injury. I’m a physician disabled from acquired brain injury. I developed meningoencephalitis while on a medical mission in Haiti. I was a busy practicing internist for almost 19 years. I loved my patients, my residents, my medical students as my extended family. I had to give up my medical practice. Now I depend more on others for help. I was hospitalized with the worst headache of my life two years ago.

A positive spinal tap, a negative cranial CT. I am grateful to be alive. It was not until I got home that I realized I could not spell physician, that I had holes in my long-term memory– not just major parts of my hospitalization but books and movies and activities from my past I could not remember. My short-term memory was even worse. I couldn’t make a cup of tea. I would lose it along the way, forget steps. It would be found outside, in my husband’s sweater drawer. My nemesis teacup became my own personal form of occupational therapy. I slurred words when tired, looked at dials upside down, could barely walk from my bed to the chair. I did not see a neurologist or have any significant neurological screening in the hospital. After I got home, I called my physician and asked if I had had encephalitis in addition to meningitis.

I pushed for further screening. She noted that if I had a certain type of encephalitis, I would be drooling and in a nursing home or dead–not a comforting thought. I was referred for a cranial MRI to a neurologist who looked first at the MRI and seeing it looked normal said, “I’m tired. You’re tired.” “Let’s forget the mini-mental status exam.” I persisted and said, “No, I need to do the mini-mental status exam.” I could not recall any of the four objects listed. I couldn’t tell why a table and a bookcase were similar.

They’re both furniture. I used to perform mini-mental status exams on my patients. I was referred to a neuropsychologist for testing, my first real insight into the extent of my deficits. I could not practice medicine if I could not remember things. This was clear from the testing. One of my physicians said, “Oh, you have chronic fatigue syndrome.” I said, “No. I know it’s my brain.” Yet I really knew nothing about brain injury, nothing about acquired brain injury, and apparently my physicians did not either. It took a year and a half and my own research on TBI before I finally found a neuropsychologist who explained that I had acquired brain injury involving the right side of my brain. Having brain injury is like studying your own medical evolving textbook. Some days are better than others. It’s like having angina of the brain.

It hurts to use it, hurts to walk, think, talk. I forget things, lose things, get overwhelmed with detail, exhausted with minimal effort. I’ve lost my sensory filters for noise, light and vibration, and I have chronic pain, headaches, neuropathy of my extremities, persistent nausea, recurrent infections and multiple endocrine problems, including hypothyroidism, hypotension that’s brain mediated. I also was put into abrupt menopause. One can learn a lot from brain injury and the plethora of manifestations. I am lucky. Having a background in medicine helped me to know that my symptoms, even though they were all in my head, were real. Knowledge is power. As medical professionals, you have the ability to help people, to offer the tools to someone with brain injury. You can be an excellent physician thinking outside of the box. You may be the first to think of brain injury in a patient.

People with brain injury often look fine. We are not. Brain injury is a devastating disease if left undiagnosed and untreated. Talking about acquired brain injury, these are other types of brain injury that also commonly come with cognitive and behavioral impairments. These include anoxic and hypoxic brain injury, meningitis and encephalitis, post-cardiac procedures, toxic and metabolic encephalopathies and post-chemotherapy. In addition, patients who have vasculitis commonly can get acquired brain injuries that will give you cognitive and behavioral impairments.

So what are some of the challenges that people with traumatic brain injury face? Certainly the sequelae of traumatic brain injury will depend on a number of factors. Their pre-traumatic brain injury level of functioning, their severity of injury, their pre-TBI personality, their types and the areas of the brain injury that are affected, the early and late treatment after injury and certainly the extent of family and community support plays an important role in people’s recovery. There are number of common physical changes that people complain of after a traumatic brain injury. Some of the most common ones include fatigue and loss of stamina, sleep disorders and headaches and chronic pain. But in addition, we see sensory changes and dysregulation of body temperature, hormonal changes, dizziness, seizures and balance disorders. Some of the common cognitive changes that we see include difficulty with attention and concentration and memory and speed of processing. This is one of the most disabling parts of traumatic brain injury overall. We also see perseveration and impulsiveness and language difficulties and executive dysfunction. Some of the social and interpersonal challenges that patients and their families have to deal with are dependent behaviors, aggression and agitation, disinhibition, denial and lack of awareness of people’s problems, personality changes and changes within the roles of family, work and the community.

Some of the emotional disturbances that we see include depression and anxiety and emotional lability, lack of motivation, irritability and difficulties with emotional control. Now we’re going to speak about the guidelines for professionals. It’s very important for us to screen for TBI, especially in the trauma patient, from falls, motor vehicle accidents and in children with failure to thrive. We need to educate patients on the resources that are available. If patients become symptomatic, we need very quickly to refer them for evaluation and treatment. Above all, we need to educate the patient and the family and the community also about the physical, emotional and memory changes that may occur over time.

It is necessary to speak slowly and clearly. Interview in a calm, non-distracting environment. Repeat requests or instructions. Give reminders and cues. Avoid open-ended questions and try to be specific. It is good to give one-step directions and requests. Have the patient make notes during contact or, if necessary, provide some written information for them. Here are some referral sources. It is important to think, suspect and do a follow-up. The signs are not very obvious in some cases. A large population is affected.

A lot of denial and minimization may exist. The brain is the center of the universe. Please protect it at all costs. I would like to thank you for your attention during this DVD. It is our hope that the information presented will increase your awareness of traumatic brain injury, the importance of screening for traumatic brain injury and to accommodate the lifelong challenges that survivors of TBI struggle with. I would like to thank our funding agency, NIDRR, for funds to create and distribute this DVD to medical and mental health professionals such as yourself. To evaluate this training, please provide your email address. Our independent evaluator will forward you a brief survey so that we can have you evaluate whether the information provided has been helpful to your own professional development. Thank you in advance for helping us with the evaluation. [♪mellow music♪].